Draft:A trustful information society

[gL.edu] This article gathers contributions by Sebastian Wiest, developed within the context of the Conceptual clarifications about "Utopias and the Information Society", under the supervisión of J.M. Díaz Nafría.

Trustful Society: Ethical Foundations and Fragilities in the Information Age

What does it mean to live in a "trustful society" in a time when trust is ever more mediated, outsourced, and monetized by digital infrastructures? This article discusses the utopian ideal of a trustful society, not simply as an emotional bond, but as a structural condition to organize human relations, institutional legitimacy, and systems of cooperation. While the notion of trust remains a fundamental pillar of political philosophy, its contemporary reconfiguration under the conditions of the Information Society necessitates new ethical frameworks and epistemological tools.

This paper importantly seeks to illuminate the emerging notion of a “trustful society" in the context of the Information Age, where trust is increasingly conditioned by digital infrastructures. Rather than interpreting trust as an emotional or inter-personal bond which can be placed conditionally, the paper analyzes trust as a structural principle required for human relations, legitimacy of institutions, and as a means for cooperation in systems. In Díaz Nafría’s concept of eSubsidiarity, trust has become a multi-layered and cybernetically distributed society of fragmented human agency, predicated on principles of distributed networks and feedback. Such architectures are also vulnerable to manipulation, especially under the clauses of Shoshana Zuboff’s "surveillance capitalism", where trust is extracted and commodified through asymmetrical data flows.

Dystopian imaginings such as Huxley’s Brave New World and Zamyatin’s We show how technocratic systems may produce a simulation of trust while managing control over epistemic inequalities that erode autonomy and disregard transparency. Also notably, trust is not dialogical or based on earned consent, but induced and engineered as a normative principle. Hence ethical distortions emerge out of epistemic inequities when the actional vision of human society becomes programmed and determined.

This paper concludes by calling for an ethical framework that is defined by pluralism, subsidiarity, and epistemic humility. Pointedly drawing inspiration from Hannah Arendt’s idea of the "space of appearance", the paper aims to construct a society where a trust can be socially built and maintained through open dialogue, shared responsibility, and democratic engagement to counter algorithmic domination and nostalgic ambivalence.

Historical Background

The idea of a “trustful society” is deeply rooted in the intellectual history of Western political thought, where it has been both a normative aspiration and a pragmatic necessity. Trust plays a crucial role in politics and philosophy because it helps determine whether a society holds together or falls apart, whether people work together freely or are forced to obey. Today, people often talk about trust in relation to democracy or technology, but throughout history, trust has always had a deeper and more complex role — it can be both a source of good and of harm.

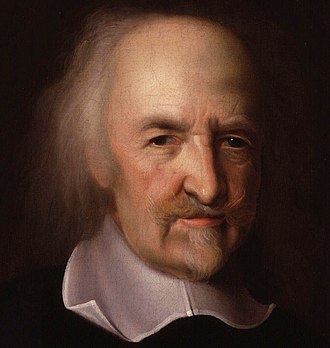

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was an English philosopher, mainly concerned with political philosophy. Hobbes gained most fame for his book Leviathan (1651), in which he laid the groundwork for social contract theory. He argued that humankind's state of nature was "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" and that humans consent to give up some of their freedom to a sovereign authority to achieve order and safety. Hobbes's work has ramifications well beyond political theory, especially regarding the state, authority, and government.

In classical political theory, trust is both a product and condition of legitimate rule. For Thomas Hobbes, who lived during a civil war, distrusting fellow citizens pushed people into a "state of nature" where mutual fear reigned and led to a war of all against all. To escape from the state of nature, citizens similarly surrendered their trust to a sovereign power that Hobbes calls the Leviathan, which has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence and provides order. Hobbes sees the nature of trust as not implicated horizontally, but vertically, as citizens surrender their trust upwards and to a central authority that arbitrates to resolve uncertainties.[1]

Jean-Jacques Rosseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and political theorist who had an impact on the Enlightenment and modern political thought. Rousseau also considered the social contract and popular sovereignty, and he argued that true political power relied upon the general will of the people.

Rousseau viewed the general will as the understanding of the understandings and values of the community as a whole. He viewed the general will as the proper locus of true trust. Rousseau argued social trust required people to dissipate their self-interests to meet the common interests of society generating both obligations to others and a moral commitment. Trust emerges in the mutuality of action on the general will, socially trusting each other to create a trusting, just, and coherent society. Therefore, trust will not develop when self-interested actions devalue and rupture social bonds orexercise distrust.[2]

Rousseau's model has potential egalitarianism, but requires a large degree of cultural and moral homogeneity - an assumption that is becoming untenable as social relationship is constituted in a pluralistic and networked society.

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) was a German philosopher, cardinal, theologian and Catholic Church official, who contributed to Renaissance humanism and early modern philosophy. Nicholas of Cusa made contributions on topics of knowledge, infinity and limits of human knowledge, to name a few.

An even earlier example of a more sophisticated distributed trust is Nicholas of Cusa, who argued that political order must needs be understood in respect to the plurality of the cosmos. He coined the term concordantia, or harmonious difference, a precursor to the principle of subsidiarity: decisions ought to be made at the lowest-highest authority given the circumstances, which places the trust dynamic in a state of uncertain trust equilibrium where agents' aspects are diverse yet interrelated. Cusa's understanding of trust supposes it arises from not uniformity or domination but through relationality of autonomy and dependence.[3]

The Enlightenment period further secularized and rationalized the concept of trust. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant emphasized trust in reason and autonomy, arguing that moral law must be grounded in rational agency rather than external authority. At the same time, the rise of the social contract tradition institutionalized trust through legal frameworks and bureaucratic systems. Max Weber later identified this process as the "rationalization" of authority, where personal trust is replaced by systemic trust in institutions, rules, and roles.[4]

In the 20th century, Marshall McLuhan and Warren Weaver explored how media technologies reshape trust at the structural level. For McLuhan, the shift from print to electronic media collapses traditional hierarchies of knowledge and authority, fostering new “tribal” forms of trust based on immediacy and connectivity.[5] Weaver, meanwhile, argued that complex societies require a new kind of “organized complexity” where trust must be managed dynamically across interlocking systems.[6]

The post-industrial turn introduces additional tensions. In neoliberal frameworks, trust becomes transactional and often subordinated to economic rationality. This commodification of trust, visible in credit scores, reputation systems, and digital ratings, alters its moral content. As Zuboff has shown, the rise of surveillance capitalism exploits affective and behavioral data to construct predictive models of trust that operate without consent or reciprocity.[7]

Thus, the historical trajectory of trust reveals a paradox: while increasingly central to the functioning of modern societies, trust has also been systematized, surveilled, and, in some cases, simulated. The idea of a trustful society remains compelling, but it must now be rethought in light of the epistemic, technological, and ethical conditions of the Information Age.

The Utopia regarding the Information Society

Utopian thought, from its origins, has been fundamentally concerned with the problem of trust. Whether in the form of divine harmony, rational governance, or communal solidarity, utopias envision societies where trust is not precarious or conditional, but embedded in the very architecture of the social order. In the context of the Information Society, this aspiration acquires new contours: it is no longer limited to political institutions or human relationships, but extends to digital infrastructures, artificial intelligence, and the automated circulation of knowledge.

The utopian horizon of a “trustful society” in the Information Age builds on several interrelated premises. First, that information transparency will lead to greater accountability. Second, that digital networks can facilitate decentralized, participatory governance. Third, that algorithmic rationality can overcome the biases and corruptions of human intermediaries. And fourth, that technological integration can foster a new form of global solidarity, rooted in shared knowledge and distributed decision-making.

These ideals are exemplified in theoretical frameworks such as eSubsidiarity, developed by Díaz Nafría, which proposes an ethical organization of complexity through informational subsidiarity[8]. In this model, trust is not a static value but a dynamic process, emerging through communicative feedback loops that allow each level of society (individual, local, national, global) to act according to its capacity and relevance. Unlike top-down or purely bottom-up systems, eSubsidiarity envisions a heterarchical structure where trust and responsibility are co-produced and context-sensitive.

This approach resonates with Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model, which conceptualizes organizations as cybernetic systems capable of self-regulation and adaptive learning. Applied to governance, this model imagines societies that maintain trust through recursive communication channels and real-time responsiveness[9]. In such systems, trust is encoded into the very feedback architecture: errors are corrected, overreach is avoided, and legitimacy is continuously negotiated.

The utopia of the trustful information society is, philosophically, situated within the values of autonomy, reason, and publicity associated with Enlightenment ideals. Societal idealization of public spheres, as both Kant and Habermas argued, is based on rational justification executed in a shared space of reciprocity and trust. New digital possibilities show that these ideals can take place in fields that suggest people participate in imagining digital systems that appear to provide, openness, transparency-by-design, and co-productive use. Projects such as Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs), blockchain voting, and open-data governing portals, illustrate this utopian aspiration: that trust can be coded with protocols and socialized intelligence.

Culturally, the imagination of trustful society can also be found on the stage of speculative fiction and philosophical utopias. Hesse's Glass Bead Game invokes a social order based on intellectual and spiritual trust (Hesse, 1943). Castalia, Hesse's fictitious province of intellectuals, can be a representation of informational virtue: a removed space from the din of politics and the marketplace, trust established through ritualized knowledge practices and deliberative discussions.

Fairly, it should be added that ecologies of trustful society do not solely represent efficiency or safety, but also meaning. They lead to a version of the world where trust is distillate of human dignity and moral growth rather than pragmatic. In a way, the utopian imagined society is essential for critical reflection on the design of digital systems. It implies trust is not limited to reliability or safety, it is at its core, a normative commitment to vulnerability and reciprocity.

However, this utopia is not without risks. As will be explored in the next section, the very mechanisms that aim to produce trust: transparency, automation, surveillance can also become tools of domination, exclusion, and epistemic closure. The challenge, then, is to hold onto the utopian vision without succumbing to its technocratic simplifications.

Dystopical Aspects

The utopian promise of a trustful society within the Information Age rests on fragile foundations. Precisely where it appears most robust. Through automation, transparency, and predictability, it demonstrates the greatest dystopian features. Digital infrastructures tend to remove the conditions that allow for trust to be established. By design, these digital infrastructures want to encode trust into the governance and interaction. The only problem for any kind of trust is that the conditions are entirely removed, including uncertainty, autonomy, and reciprocal recognition. This allows what should be trust to be replaced with a simulation of trust: authoritarian, unreciprocated, and its own form of opacity.

One of the most critical analyses of this transformation is found in Shoshana Zuboff’s concept of surveillance capitalism[10]. Here, trust is not cultivated through dialogue or reciprocity but extracted through asymmetrical data flows. Users disclose their preferences, emotions, and behaviors, consciously or not, while the systems they interact with remain largely inscrutable. These behavioral residues, or “behavioral surplus,” are then repurposed to train predictive algorithms and influence future behavior. Thus, trust is reduced to compliance, and participation becomes a resource for manipulation.

Brave New World (1932)

This dynamic is powerfully illustrated in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which trust is engineered through pharmacological and institutional means. Citizens are conditioned from birth to embrace the world as it is, to love their servitude, and distrust their own critical faculties. The result is not the absence of trust but rather its complete domestication. In those societies, trust acts not as an ethical relation, but as a tool of pacification—a form of affective anesthetic that makes dissent unthinkable.

By contrast to conventional notions of trust, which imply that there exist mutual abilities to recognize autonomy and moral responsibility, domesticated trust in Brave New World is both uni-directional and manipulative, encouraging complacency and discouraging skepticism, and thereby removing the conditions to allow trust to serve as a basis for social cohesion. An actuated critical faculty is not generated through external coercion and the threat of physical violence or fear, but is created internally when feelings of contentment and conformity are overwhelmingly proliferated. The consequence is that trust becomes the most subtle yet infinitely powerful form of domination, an affective anesthetic that ultimately makes dissent unthinkable, and radical change impossible.[11]

We (1920)

Similarly, in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, trust is effectively raised to the level of a sacred principle or a principle for ordering a totalitarian state. The regime, represented by the mysterious “Benefactor,” aims to eliminate uncertainty and ambiguity through radical transparency at the everyday level. Citizens live in glass houses, where every action and word is observable by the collective “eye,” indicating that all personal secrets and privacy have been stripped away. We learn that our emotions are not ours to do as we please with but are relegated from the state, become programmed into schedules and formulas, for the purpose of advancing productivity and harmony in society.

By implementing the idea and practice of radical transparency, what the “perfectly transparent society” does is redefine trust as visibility and predictability. The assumption taken here is that once secrecy and hidden motives have been eliminated from society, it can operate in a predictable and flawless cooperative fashion. Trust gained from the totalitarian regime comes at a price, because when the social order is subjugated completely to the collective will, freedom, spontaneity, and dissent are crushed. Society effectively becomes mired in a technocracy that subjugates desire, identity, and authentic relationships to the “eye” of servitude and observation, where trust is merely a byproduct of compliance.

Zamyatin’s We reveals some dystopian implications to our contemporary calls for “radical transparency” in political and social discourse. Public transparency is often hailed in the name of combating corruption and restoring the good graces of trust, but We highlights that the uncurbed pursuit of transparency can become just as oppressive. Without reservation that visibility becomes another form of control in a regime where the constantly observed submit to the powerful mimicry of the eye, there is loss of difference in a homogenized space. The irony is that this type of transparency creates a fear that trumps trust in a maturity that does not invite mutual respect and freedom.[12]

Rethinking Trust in Technological Societies

Even systems that seek to promote trust for good (e.g. reputation scores, blockchain verification, or "smart" AI governance), might also be dystopian. They become calculable, measurably calculable risk that can be trusted; they may transform trust into calculable risk. This can allow for greater reliability but diminishes the moral and relational aspects of trust. In most instances, inequalities are then exacerbated — those who are already poorly trusted as a relationship may find it more difficult to prove they are trustworthy, recognizing underlying algorithmic functions also carry biases from history.

By perceptually changing trust to calculable risk, these systems underline predictability and control rather than empathy, forgiveness or ethical judgment. The instrumentality of this situation, as with all new divides of control and incorporation, is that trust becomes commodified, is meant to be returned and is measurable rather than an ethical disposition with respect to our ability to be vulnerable in a shared context. Moreover, as trust becomes commodified, it is reformulating the dynamics of the transaction between person and person, and institutional form, the gap between account and nuance is pried open into our engagement as points of data. This ultimately risks diminishing trust to only being a point of location.

Additionally, the purported neutrality of any kind of digital infrastructures can mask the appalling asymmetries of power that are still at work. What we perceive as an equal disappointing potential of agency is often areas where we help centralize authority as we spread epistemic power into an overhaul of responsibility. As Díaz Nafría has discussed in his work navigating the "cybernetic panopticon"[13], to see a boring figure, the citizen still plays a role in our humanized version of being "humanly" bounded by the technology of a system that continues to operate towards a future predefined by rules and whitelisted interests.

Within systems where trust becomes coercive - i.e. demanded, designed or compulsively enforced rather than freely situated, the orientations to the ethics of making trust coercive become ripe with diminution - trust becomes disciplinary - citizen surveillance of trust instead of being dialogical or relational, this process onboards trust as a configured timing piece to identify relationships of governance, optimization and control.

Ultimately, the dystopia of the trustful society, reveals the zeitgeist of technological overdetermination. In the hyperstdial of trust becoming problematized in terms of solvable relationships through code, circumspect behaviors, or layers of surveillance to mitigate risk, then cede the risk, judgment, and feelings of moral ambivalence. The value of trust is that it is not guaranteed, and the very fact of requiring trust, is what always uses history, feels value, and is congenitally vulnerable. Ending the need for open possibility means securing efficient, smooth, celery life, but the absence of trust would lean toward being good society, rather than finally being human in the spirit of sociability.

References

- ↑ Perry, J., Bratman, M., & Fischer, J. (2015). Introduction to Philosophy: Classical and Contemporary Readings. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Miller, D. (2003). Political Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Díaz Nafría, J. M. (2017). Cyber-Subsidiarity: Toward a Global Sustainable Information Society. In Handbook of Cyber-Development, Cyber-Democracy, and Cyber-Defense.

- ↑ Craig, E. (2002). Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ McLuhan, M. (1962). The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Weaver, W. (1948). Science and Complexity. American Scientist, 36, 536–544.

- ↑ Zuboff, S. (2015). Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30, 75–86.

- ↑ Díaz Nafría, J. M. (2017). eSubsidiarity: An Ethical Approach for Living in Complexity. In The Future Information Society: Social and Technological Problems (pp. 59–68).

- ↑ Díaz Nafría, J. M. (2017). Cyber-Subsidiarity: Toward a Global Sustainable Information Society. In Handbook of Cyber-Development, Cyber-Democracy, and Cyber-Defense.

- ↑ Zuboff, S. (2015). Big Other: Surveillance Capitalism and the Prospects of an Information Civilization. Journal of Information Technology, 30, 75–86.

- ↑ Huxley, A. (1958). Brave New World Revisited. Harper & Brothers.

- ↑ Zamyatin, Y. (1924). We. E. P. Dutton & Co.

- ↑ Díaz Nafría, J. M. (2017). Cyber-Subsidiarity: Toward a Global Sustainable Information Society. In Handbook of Cyber-Development, Cyber-Democracy, and Cyber-Defense.